The following is an except from What a Building Does: The Hoosier Modernisms of Evans Woollen (, 2025). Written by Phillip Cox with photographs by Niall Cronin, the book is the first biography of Evans Woollen, Indianapolis's leading modernist and an unsung figure in postwar American architecture.

BOOK EXCERPT What a Building Does: The Hoosier Modernisms of Evans Woollen

Author

Phillip Cox and Niall Cronin

Tags

A Portrait of its People: St. Thomas Aquinas and the Church Architecture of Evans Woollen

Architect Evans Woollen (1927-2016) made a profound contribution to the built identity of Indianapolis, Indiana, his hometown. Most recognized for introducing concrete Brutalism to the city, his practice ranged from significant public buildings to single-family homes, theaters, schools, master plans, and historic renovations. But churches were also a vital part of Woollen’s sixty-year career and, at least initially, where he did some of his most boundary-pushing work. As an architect he was intrigued by the spiritual possibilities that churches offered, where ancient ritual and modern design might merge to create a uniquely moving experience for the end user. Their significance transcended the more earthly concerns with which his other projects were usually preoccupied. “Churches are . . . so satisfying because in an unexpressed way one is almost always sure that the people you’re working for want something very good in a kind of selfless way,” he once told critic Esther McCoy. “And that’s inspiring to an architect beyond the desires of a banker or a school superintendent.”(1)

St. Thomas Aquinas Church, completed in 1969, offered such possibilities. Commissioned by a politically progressive Catholic parish on Indianapolis’s north side, the project consisted of a new sanctuary building to replace an older wooden structure that had long outserved its use. Church leaders gave their architect a tiny budget of only $300,000. Woollen nonetheless made the most of it, producing an unusual but brilliantly austere design well suited to the more relaxed Catholic services of the 1960s. “We studied pretty carefully what we thought the Second Vatican Council would propose as a new Catholic Liturgy. And we might be responsible for setting a new pattern within the church,” Reverend Joseph Dooley, the church’s priest, told the Indianapolis Star at the time.(2)

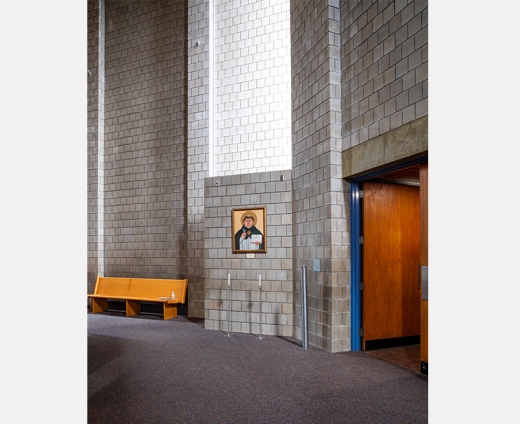

Although the church’s exterior has since been substantially altered, its original appearance was undeniably avant-garde. There was no steeple or stained-glass windows or grand front steps leading to a large wooden door. Instead, a vaguely trapezoidal mass, mysterious and fortresslike, sat at the far end of a small concrete court that doubled as a parking lot on Sunday mornings. Interceding brick planes composed its geometric and largely windowless facade, giving little indication of what went on inside. If the building was indeed a church, it was missing the usual markers that had defined religious architecture for centuries. “A church is a portrait of its people at a particular moment in time,” Woollen was quoted as saying at the building’s dedication.(3) There could be little doubt that St. Thomas was a modern church for a modern congregation.

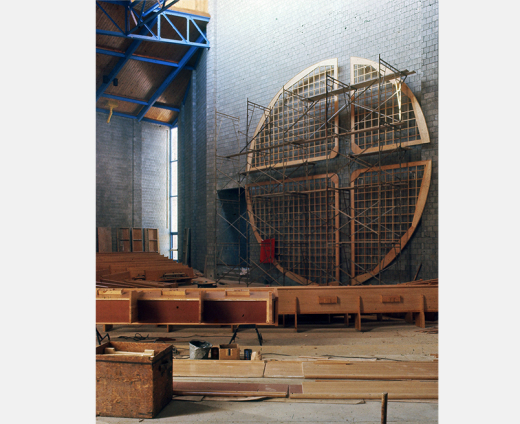

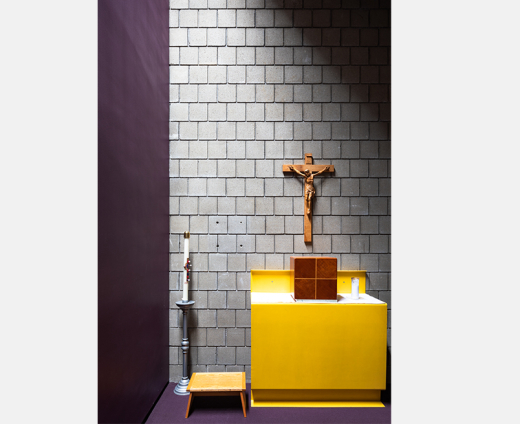

While the exterior appeared impenetrable, the interior was surprisingly transparent. Entering through a compressed entry portal appended to the building’s southeast side, the congregant emerged into a soaring, columnless sanctuary made of plain concrete block. The space was surprisingly well lit; sunlight filtered in from thin, vertical windows hidden between the meeting points of the exterior walls. Overhead a massive, cobalt-blue metal truss supported a ceiling clad in wood planks. Additional bits of exposed plumbing were painted a cheerful canary yellow. Diverging from the familiar cruciform plan of traditional church architecture, rows of pews were fanned around a simple raised altar to form what the firm described as a “liturgical theater” in the style of a bowled amphitheater.(4) On Sundays, mere feet separated Reverend Dooley from his flock. And because there was not a conventional proscenium or altar rail, congregants stood to receive communion rather than knelt.

​â¶Ä‹

All these elements bucked years of architectural convention. But the church’s most radical feature by far was the thirty-foot-tall cross floating against the altar wall. Designed by Peter Mayer, a young architect in Woollen’s firm, the cross’s four metal panels formed the sanctuary’s only religious icon, an abstracted crucifix composed by negative space. Its asymmetric design and brilliant, crimson color made an indelible statement – part sculpture, part set design, part shrine. The total effect was pure drama, especially when the piece was illuminated by the perfectly angled spotlight cut out of the church’s ceiling. “I don’t know how Evans was able to talk the church into accepting it,” said Mayer, who fabricated the cross’s panels himself.(5) Mayer also designed matching stainless steel altar furniture to complete the sanctuary’s spare aesthetic. The furniture was modular and removable so the sanctuary could double as a venue for secular concerts when desired.

The St. Thomas project demonstrated several themes that were coming to define Woollen’s practice: the choreography of light and color in space; the integration of art, graphics, and furniture within a project’s overall design; and, most important, a sincere concern for how a building would affect the people meant to make use of it. Utilizing industrial materials and exposed structures, St. Thomas offered an intentionally raw and unmediated environment for worship. “Cannot the inside be what things are? The outside is slipcovered to please the neighborhood, but on the inside you’re face to face with God – or want to be,” said Woollen about the project later.(6) By slipcover, Woollen meant the red brick that clad the building as opposed to its concrete skeleton left exposed inside the sanctuary. Recalling Louis Kahn’s First Unitarian Church of Rochester, Woollen would also employ a similar material palette for a library project at Marian University in Indianapolis, designed around the same time.

In Indiana as well across the broader Midwest, church architecture was a surprising site for architectural experimentation. Churches proliferated during the postwar building boom, especially in growing suburbia, and modernism flourished among new and progressive congregations. About an hour’s drive south of Indianapolis there was Eliel and Eero Saarinen’s First Christian Church, one of the nation’s earliest examples of modern church design and a major influence on church architects everywhere. With its gridded facade, totem-esque bell tower, and large reflecting pool, First Christian made headlines for being both shockingly new and shockingly expensive. “The costliest modern church in the world, planned by Europe’s most famous modern architect and his son, is going up across the street from a Victorian city hall and a conventional Carnegie library in Columbus, Ind,” Time reported as construction was underway. “It is a simply designed church for a simple people,” Eliel Saarinen explained to the magazine.(7) Indianapolis residents unable to make the trip to Columbus could inspect plans for the design themselves when the exhibition Architectural Designs and Models by Eliel and Eero Saarinen opened at the John Herron Art Institute that same year.

First Christian Church may have been the most famous modern church in Indiana, but it was far from the only one. Other churches across the state, like the triangular sanctuary of Concordia Theological Seminary (1957) in Fort Wayne by Eero Saarinen, the swooping St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church (1958) in Gary by Edward D. Dart, or the translucent First Missionary Church (1960) in Berne by Orus Eash, showed just how creative religious architecture could be. In Indianapolis proper there was St. Rita’s Catholic Church (1958) by Charles M. Brown and Holy Trinity Hellenic Orthodox Cathedral (1960) by McGuire and Shook Compton, Richey and Associates, both of which featured free-standing slab bell towers and geometric brickwork. Woollen would have also been well acquainted with Christian Theological Seminary (1966), designed by New York architect Edward Larrabee Barnes and funded by Miller’s family foundation. Located on thirty-five acres south of Butler University, the complex made an impressive case for the unique potential of modernism in religious architecture, and its spartan yet elegant appearance was well publicized by the press. “Like other architecture that departs from the familiar, [the seminary] will be seen differently by different people and, most likely, it will take a bit of getting used to,” reported the Indianapolis News.(8)

Like St. Thomas, many of these churches emphasized informality and communal intimacy as a means of heightening one’s relationship with God. Their goals were often expressed through the use of simplified forms; raw or unadorned surfaces; and more egalitarian, in-the-round plans. Woollen began his own church architecture career in 1963 with an almost-primitive design for St. Thomas Lutheran Evangelical Church in Bloomington, Indiana, fifty miles south of Indianapolis. Built for $40,000, Woollen likened the church’s wooden construction and dramatically pitched roofline to the rustic stave churches of medieval Europe. St. Timothy’s Episcopal Church, completed in 1969 on Indianapolis’s outskirts, followed a similar model, its exaggerated, angular profile recognizable from all directions. Like St. Thomas, both churches featured centralized plans, a feature increasingly common in modern church architecture by the late 1960s.

The rock-bottom budgets Woollen often contended with were not atypical for small congregations, and more than once did the architect’s design ambitions strain what a cash-strapped building committee could feasibly accommodate. A review of Woollen’s church designs from the 1960s shows several instances of highly unorthodox, even fanciful schemes that were never completed as planned. For Asbury United Methodist, Woollen imagined a multibuilding campus of Seussian A-frames, with the height of a roof’s pitch representing the relative importance of the building’s function. For Warren Hills Christian, a young congregation that had previously met in a shopping mall, he envisioned two geometric saucers, each topped with a spire. Perhaps the most elaborate scheme was for King of Glory Lutheran Church, where Woollen proposed a honeycombed plan of hexagonal rooms clustered around a central plaza. Echoing again the work of Kahn, the plan had a “techno-organic” tone rarely seen in Woollen’s output.(9) Renderings were published both locally in the Indianapolis Star and nationally in Arts & Architecture magazine, but when the church finally opened in 1963 its design was considerably toned down. The reason may have been just as much about cost as the radicality of its grandiose design. At the time Lutheran church designs needed to be approved by the denomination’s governing body in New York City. Confident in his idea and with the backing of the congregation itself, Woollen traveled there to present his plan, but the scheme was ultimately rejected. The architect took the setback in stride, reasoning that the design’s conceptualization and subsequent publication was a reward in and of itself. “I try to take this view of things that all of one’s work may not be built,” he said. “But it is not a loss. It has a place. It may even be best that all of one’s work may not be built.”(10)

Except for a freestanding bell tower (Woollen, ever the romantic, referred to it as a campanile) originally planned for the church’s left flank, St. Thomas came to fruition relatively intact. And if Woollen heard any grumblings from parishioners about the church’s bare-boned aesthetic, he kept those critiques to himself. “I can’t imagine the priests really liked what we were doing, but I never heard anything about a controversy. But there must have been,” Mayer recalled.(11) The project earned positive press coverage locally and nationally, as well as an honor award from the Indiana Society of Architects. But perhaps the most meaningful review came a few years later from Reverend Dooley: “The building looks good only where there are people in it. That says something too, that we don’t mind.”(12)

About the Authors

Phillip Cox is a writer and native Hoosier. He now lives in New York City where he previously worked for the design firm Pentagram.

Niall Cronin is a photographer in New York City. Born in Indianapolis, his work has been shown at the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art (iMOCA) and Edington Gallery. He's been published in the Financial Times, Fast Company, and Time Out.

References

1 Evans Woollen, interview with Esther McCoy, between 1964 and 1980, Esther McCoy papers, circa 1876–1990. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

2 Philip Allen, "St. Thomas Church Design Primitive," Indianapolis News, March 7, 1970.

3 "A Church for the Revised Catholic Liturgy," Architectural Record, February 1970, 120.

4 "St. Thomas Aquinas Church Project Description," Box 2, Folder 9, Woollen, Molzan and Partners, Inc. Architectural Records, CA, 1912–2011, Indiana Historical Society.

5 Peter Mayer, interview with the authors, June 30, 2023.

6 Robert Benson, "An Architecture of Engagement: The Work of Evans Woollen," Inland Architect, July/August 1987, 58.

7 "Piety in Brick," , January 27, 1941.

8 Fremont Power, "Seminary Is Severe, But Warm," Indianapolis News, April 4, 1966.

9 For Kahn's use of hexagons, particularly in religious projects, see Sarah Williams Goldhagen, Louis Kahn's Situated Modernism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 64–101.

10 Woollen, interview with McCoy, between 1964 and 1980.

11 Mayer, interview with authors.

12 Philip J. Tounstine, "Evans Woollen: From Controversy, Effective Architecture," Indianapolis Star Magazine, May 8, 1976, 20.